Chinese children’s voices

China’s recent economic boom and rapid urbanisation owes much to the migration of workers from rural areas to the cities. By 2018, for example, over 200 million rural migrants worked away from their home villages and over 61 million rural children – equivalent to the population of Great Britain – had at least one parent who had migrated without them, leaving them typically in the care of grandparents or other family members. In many cases, both parents had left to work elsewhere.

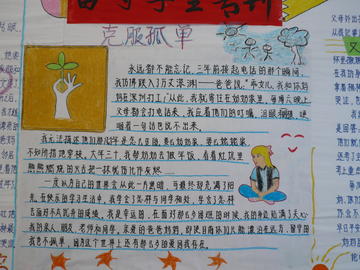

'Conquering loneliness', an essay by a child whose parents both work in Shenzhen, is displayed on the wall in a rural school's activity room for left-behind children

The impact of this great migration on childhood and on family relationships in China has been explored by Rachel Murphy, OSGA’s Professor of Chinese Development and Society. Her unique approach to the situation – interviewing the ‘left-behind’ children themselves over a period of years – is attracting interest in Chinese academic and policymaking circles, as well as from international organisations like UNICEF. It is rare for migration, urbanisation and family change to be explored through the eyes of children and for children’s voices to be brought into conversations about national strategies for capital accumulation in a wider context of global market integration.

In 2010 and 2011, Rachel interviewed 109 children aged between 9 and 17 in Anhui and Jiangxi, two major labour-exporting provinces in China’s interior. Most of these children had at least one parent who was or had been a migrant worker since they started school. She also separately interviewed their caregivers – most commonly a grandparent or an at-home parent. Between 2013 and 2015 she carried out follow-up interviews with 25 of the younger children (now teenagers) and their caregivers, investigating how their circumstances and views had evolved. She also spoke to rural teachers and visited migrant parents in the cities.

‘In the provinces where I conducted fieldwork, parental migration had become a “new normal”, with over half of children having at least one parent who had migrated without them,’ says Rachel. ‘It was clear that parental migration profoundly changed children’s relationships with the adults in their families. The children were all socialised to see their parent’s migration as generating an intergenerational debt for them to repay through study, and educational aspirations for the children were clearly linked to the family’s migration project.’

The influence of cultural attitudes to gender on children’s views about their circumstances was also apparent. For instance, children whose mothers had migrated could feel especially let down because their perceived natural caregivers had ‘dumped’ them. Children of home-alone fathers with migrant mothers also recognised that their parents faced social censure because gender norms prescribed a breadwinner father.

Helping grandma: a long day at school is followed by domestic tasks, before evening revision classes back at school

‘I also saw that education pressures on children were inflected by the circumstances of parental absence,’ notes Rachel. ‘In primary school, the parent-work-and-child-study bargain gave many of these children a focus and way to deal with the pain of missing their migrant parent, but as they grew older, and especially if their grades were mediocre – which could result in harsh physical discipline from parents – they became disillusioned and teenage resentment could become acute.’She adds: ‘Overall, I was alarmed to see just how hard and how much people of all ages in and from rural China worked and how tired they all seemed, both physically and emotionally. Children worked from early in the morning till late in the evening, attending revision classes at school after dinner. At the same time, everyone was so fixated on their family obligations and on their hopes for security and a better future for the next generation that they did not question the material and social practices through which their lives were organised or the immense sacrifices that they incurred. Family and national strategies for rapid capital accumulation intertwined seamlessly.’

As demonstrated in Rachel’s new book, The Children of China’s Great Migration, when the education system is oriented towards equipping children to become a ‘worthwhile’ person via competition and reproducing hierarchies – rather than nurturing potential and promoting a love of learning – millions of children become alienated, written off and destroyed. China’s rural children have little opportunity to access learning-oriented education and there are few possibilities for them to pursue plural routes to learning or to construct viable identities for themselves. Even those who spend their two-month school summer break in the city visiting their migrant parents are prone to find themselves locked in a room with a television and homework books while their parents work long hours. They see little of city life.

‘My research demonstrated that rural children disproportionately shoulder the emotional costs of a labour migration regime premised on the long-term separation of families whereby the urban employers and municipal governments do not need to pay a full family wage to migrants or provide them with public services because the children are fed, educated, housed and raised in the countryside,’ says Rachel. Their hard lives notwithstanding, some left-behind children still liked to make fun of her: ‘I asked one boy what his three wishes in life were and he replied, “To grow big feet and squash anyone who asks me what my three wishes in life are” .’

The Children of China’s Great Migration by Rachel Murphy is published by Cambridge University Press . The writing of this book was made possible by a British Academy Mid-Career Award.

Read more about Rachel’s work here.

Read other Impact Spotlights here